The waiters cannot be coaxed, frightened or bribed.

This I explain at length, but to no avail. Then follows a search which usually ends in my finding that I have left my bread card at home or in my other coat. ‘All right,’ I say, ‘In a minute let's have one of those rolls.’ ‘Card first,’ says he and moves the plate still farther back. “‘Your bread card please,’ says the waiter and at the same time deftly withdraws the plate of bread for which I am reaching.

was still neutral) and published 100 years ago today: “Economic Conditions in Germany (part II): A Great National Bread Trust.” There is a charming vignette to begin the tale: Some scholars argue that food was scarce but not critically so, but there’s an interesting statistic in a 2003 article by William Van der Kloot that shows the lack of food for people and cattle alike: the average weight of cattle at slaughter dropped from a prewar high of about 550 pounds to a low in 1918 of about 300 pounds.Īgainst that background, there’s the hopelessly optimistic article from Scientific American written by American citizen, Albert K.

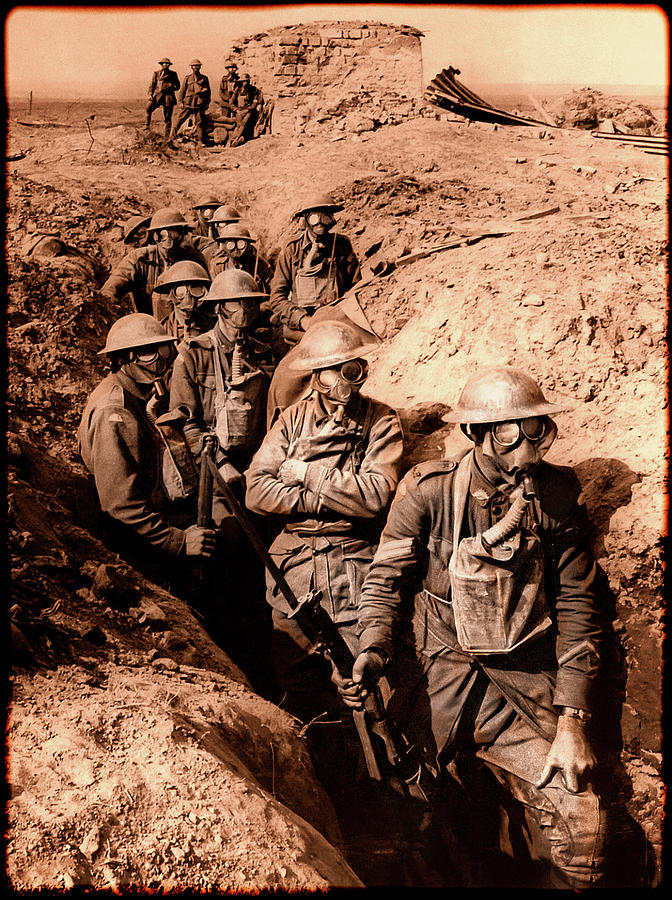

Alexander Watson in his book Ring of Steel noted that “Germany teetered on the brink of starvation during the second half of the war.” The blockade on imports and exports imposed by the British (and enforced by the Royal Navy) at the start of the war in 1914 is mostly to blame. The civilian population called it the “turnip winter,” a bitter nickname, given the indignity of having to eat turnips, normally considered to be food fit only for cattle. Wartime food shortages in Germany in the winter of 1916–1917 were terrible.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)